I stopped posting on this blog more than a year ago, but in the last couple of days, I’ve had a strong urge to reopen it. I don’t know if anyone else will even read this, but as I reflect on the election of our first African-American president, I am been inspired to write something for public consumption. Given what it used to be, I thought this an appropriate forum.

Yes, we can.

Obama’s signature line, which clearly resonated with so many Americans, sums up what his campaign was all about. With his promise of “change,” he managed to turn out millions of new voters, most of whom seem to view him as the last great hope for a much-needed national revitalization project. Political buzzwords aside, many Americans–especially the ones that did support Senator Obama–expect a change not only in policy, but in the relationship between the American people and their government. “I’m asking you to believe,” reads the quotation from the top of Obama’s campaign website. “Not just in my ability to bring about real change in Washington… I’m asking you to believe in yours.”

Yes, we can.

To many in the African-American community, it seems that “we can” represents the logical culmination of “we shall”–as in “We Shall Overcome.” To see John Lewis and Jesse Jackson choking up and shedding tears on national television makes this link obvious. With that said, I was actually rather surprised by the media’s extraordinary focus on race in the immediate aftermath of the election. Of course, it’s to be expected given that we have elected the first African-American president in our nation’s history. The magnitude of that fact simply cannot go unrecognized. It is an extraordinary event, and as such, it deserves extraordinary coverage.

But at 11:00 pm on Tuesday night, just after they called the crucial West Coast states for Obama, the media (MSNBC, at least) chose to portray the victory celebration in a curious way. Immediately, they cut to Atlanta, flashing scenes of all-black crowds at Spelman College and Ebenezer Baptist Church across the screen. In doing so, they seemed to portray African-Americans as a group still somehow “apart” from American society. Perhaps it’s naive–especially for a historian of the South–but to me this seemed somewhat amiss.

I certainly don’t mean to imply that race was not a factor in this election. To anyone who understands “the arc of history” (in Obama’s words) in even the crudest of terms, it is undeniable. If you doubt it, take a look at the maps below.

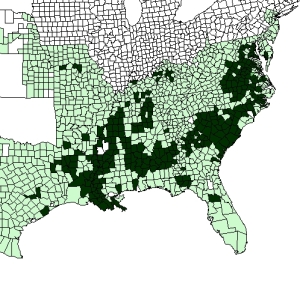

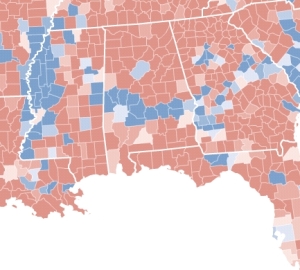

The first map (courtesy of the University of Virginia’s Historical Census Browser) is of slave population by county in 1860. The counties in the darkest shade of green all had more than 5000 slaves just prior to the Civil War. The second map (courtesy of the New York Times) is of counties in the Deep South where Obama won a majority of votes on Tuesday. The connections should be apparent, and we know from exit polls that Obama received upwards of 95% of the “African-American vote” nationwide. Of course, Obama won none of these Deep South states, and perhaps that says something about American society in the 21st century, but I’ll leave that for another day.

Nevertheless, Obama ran not as an “African-American candidate,” but as an American candidate who happened to be of African descent. (I could make a tenuous claim about the political necessity of such a strategy and what that might say about American society, but I’ll leave that for another day as well.) Instead, at the risk of sounding more controversial than I really intend to, what I will say is this: those shots of Spelman and Ebenezer are not indicative of the “change” that Obama really represents.

I certainly understand the symbolism of Obama’s victory to African-Americans, and they have every right to celebrate this victory as their own. They have overcome, and so in a sense, we have all overcome. For that reason, November 4th, 2008 will go down as an important day in American history.

But the true genius of Obama’s campaign–and the reason for its tremendous success–could be seen not in Atlanta, but in Chicago’s Grant Park, where nearly a quarter of a million people celebrated victory. The crowd in Chicago included many prominent African-Americans, but it also represented a true cross-section of the American electorate. Citizens of every race, class, gender, religion, sexual orientation, and age showed up to show their support.

Unreconstructed rebels may take issue with this next claim, but it’s only fitting that in a park named for a man whose military efforts helped end the Civil War and made it possible to put our great nation back together, Obama promised the American people–in terms that sounded not unlike Martin Luther King, Jr.–that “we will get there.”

In an interesting op-ed from earlier this week, John McWhorter suggests that of all the issues facing the United States today, racism is relatively low on the list in terms of urgency. “America has problems,” he writes, “and our new president knows it. However, is America’s main problem still ‘the color line’ as W.E.B. DuBois put it 105 years ago? The very fact that the president is now black is a clear sign that it is no longer our main problem, and that we can, even as morally informed and socially concerned citizens, admit it.”

McWhorter’s intent is not to deny the existence of racism in the U.S. Instead, he argues that American attitudes toward race have changed such that racism has become socially unacceptable, that out-and-out racists, while still around, have been pushed to the fringes of society. “[Y]esterday,” he writes, “we saw that this ‘out there’ brand of racism cannot keep a black man out of the White House. . . . Sure, there are racists. There are also rust and mosquitoes, and there always will be. Life goes on.”

He points out that when asked for his immediate reaction to Obama’s victory, John Lewis described it as “amazing–almost unreal.” McWhorter, however, concludes that “There is nothing at all ‘unreal’ about this. It is, after all, what we were supposed to be working toward. We must embrace it.”

Should we acknowledge that, even with the election of our first African-American president, racism still exists in our nation? Of course we should. But can we also say that the election of Barack Obama is proof that we, as Americans, have the capacity to set race aside and come together in the best interest of our shared future? Can we say that racial differences no longer define our nation?

Yes, we can.